How pioneer Japanese alpinists weighed into the great debate over Japan’s vanished glaciers"Viewed from afar, the gentle lines of its skyline suggest a serene and settled character. The splendid accents of the ridgeline save the mountain, despite its huge mass, from any hint of ponderousness. These accents are the three cirques that carve deeply into the upper slopes, adding to their form a note of tension … The snow lingers longer in these amphitheaters, outlining them crisply." (

Nihon Hyakumeizan, Senjō-dake)

![]() |

| Senjō-dake (photo courtesy of Yama to Keikoku) |

When writing up Senjō-dake, a mountain in Japan’s Akaishi range,

Fukada Kyūya (1903–1971) pays tribute to the mountain’s elegant cirques. But no guess is hazarded as to how these “splendid accents” could have formed. Fukada may have had reason to avoid this question. For cirques like these lay at the focus of a long-running controversy that lasted well into the writer’s own lifetime. And, like Fukada himself, several of the protagonists were members of the Japanese Alpine Club.

It was Yamasaki Naomasa who started this one. As we have seen in a

previous post, it was in the summer of 1902 that the young geographer discovered evidence for an ancient glacier beside Shirouma’s Great Snow Valley. And, on returning to Tokyo, he wasted no time in announcing his findings.

![]() |

| Evidence for ancient glaciers? The striated "Red Rock" on Shirouma |

Asking rhetorically, “Did Japan really lack glaciers?” (氷河果たして本邦に存在せざりしか), Yamasaki’s public lecture sent a frisson through academic circles. A summary that appeared in a newspaper article was translated into English – by a Bank of Japan official, no less – and picked up in the

February 1903 edition of Science, then as now the most prestigious of scholarly journals.

Alas, few accepted his arguments. Where in Japan, they asked, do you see obvious moraines and deep “drifts” of pulverised rubble –the debris that clearly marks the paths of ancient glaciers all over the Alps or the Himalaya? Undismayed, Yamasaki continued to press his case. In a second public lecture, delivered in September 1904, he suggested that ancient glaciers might have honed the razor-sharp ridges of Yari-ga-take and other high mountains.

![]() |

| Side moraines on the Morteratsch glacier, Switzerland |

Still, his peers were underwhelmed. In 1911, the palaeontologist Yokoyama Matajirō published a paper on fossils from the Bōsō Peninsula that purportedly showed that Japan had enjoyed a tropical climate during the Ice Ages. Two years later, this conclusion was overruled by another geologist, Yabe Hisakatsu, who found that the fossils dated from after the Ice Age. But, still, nobody could find the missing moraines and drifts.

![]() |

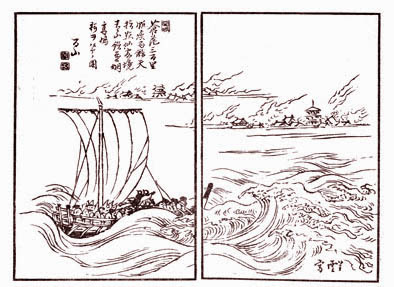

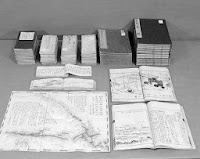

| Sangaku: the first edition |

Given the orographic nature of the subject matter, it was all but inevitable that the debate would spill over into “Sangaku” (‘Mountains’), the journal of the newly formed Japanese Alpine Club – which Yamasaki had joined within a year of its inauguration. Indeed, Yamasaki had contributed an article on the snows of the high mountains (高根の雪) to the very first volume of “Sangaku”, published in 1906.

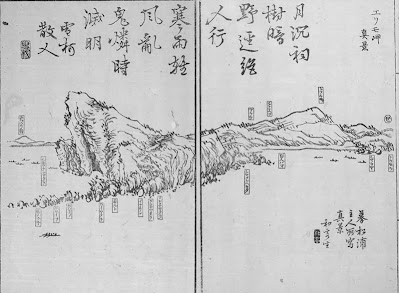

But Yamasaki was not party – at least, directly – to the controversy launched in the same pages a few years later. In the November 1911 edition, two articles were published, one putting the case for ancient glaciers and the other opposing it. The first, (日本アルプスと既往の氷河) argued that former glaciers had carved out the shapely cirques found on many high ridges throughout the Japanese Alps. A map was included of these suspected glacial landforms, the first ever attempted.

The author was Tsujimura Tarō, then a 21 year-old university student. Tsujimura’s enthusiasm for mountains was such that he too had joined the Japanese Alpine Club just after its inauguration, making him its youngest member. If his “Sangaku” article read like an uncritical redaction of Yamasaki’s views, this should not be surprising: on entering Tōkyō University, Tsujimura had immediately started attending the professor’s lectures.

In 1911, the editor of “Sangaku” was Kojima Usui, the banker and part-time writer who, six years before, had brought together the founding members of the Japanese Alpine Club. Kojima had taken a close interest in Yamasaki’s theories since 1902 and made a point of attending his public lectures. Yet he never allowed his personal friendship with the geographer to sway his independent judgment on the glacier question.

As editor, it is likely that Kojima had the chance to see Tsujimura’s contribution before setting down his own views. His own piece, which was placed after Tsujimura’s, dealt ostensibly with the permanent snowfields of the Japan Alps, with reference to the Hodaka massif, the 3,000-metre peaks that anchor the southern end of the Northern Alps range (日本アルプスと万年雪関係附穂高山論). Effectively, though, Kojima delivered a 29-page rebuttal of Tsujimura’s 19-page article.

![]() |

| The Hodaka massif from Tokugo Pass |

Japan’s cirques were formed differently to those of Europe, Kojima noted; their headwalls were less steep, implying that permanent snowfields, not glaciers, had carved them. In this, he followed John Tyndall (1820–1893), the British physicist and pioneer alpinist, who had proposed that snowfields could slip downhill like glaciers, imitating some of their erosive powers.

As for the moraines and the striated rock that Yamasaki had found on Shirouma in 1902, Kojima hadn’t seen them for himself and so he wasn’t able to judge their worth as evidence for ancient glaciers. And he concludes by suggesting that his fellow Japanese alpinists should take up the search for moraines and other glacial landforms.

![]() |

| Yamasaki Naomasa |

In the re-worked version of the article that appears in his collected works, Kojima added a further argument. Japan’s volcanic craters, he observed, only retain their pristine shape if the parent volcano is still active; the moment a volcano falls silent, erosion starts to destroy its features. By the same token, Japan’s cirques are too crisply defined to have been created by glaciers that vanished 20,000 years ago; instead, they must be the product of some continuing agency – namely, the perpetual snowfields that scour them.

At first sight, Kojima’s scepticism seems difficult to explain. After all, the banker was just then tirelessly

promoting “The Japanese Alps” as a term for the high mountains of central Honshū. In fact, he’d chosen the title “Nippon Arupusu” to adorn his collected mountain writings, of which the first volume came out in 1910. Not all his peers welcomed this neologism. Yet evidence for ancient glaciers could only have strengthened the case for awarding the alpine brevet to the Hida, Kiso and Akaishi ranges.

Could it be that Kojima picked up his glacial scepticism from

Walter Weston (1860–1940), the English missionary and mountaineer? The question is raised by Ono Yugo, Japan’s pre-eminent glacier expert of modern times, whose paper on the 1911 Sangaku debate is the main source for this post. Kojima certainly did take over the concept of the Japan Alps from Weston, who had embedded them in the title of his own memoirs –

Mountaineering and Exploring in the Japanese Alps, published in 1896.

It was Weston too who, on his second visit to Japan, had originally suggested the idea of an “Alpine Club” to Kojima. The proposal was floated during a conversation over a pot of tea at Weston’s flat in Yokohama in early 1903 and the club itself was formed two years later, in October 1905. For this contribution, the newly formed “Sangaku-kai” or Japanese Alpine Club promptly elected the Englishman as its first honorary vice-chairman.

![]() |

| Walter Weston |

When it came to ancient glaciers, Weston was firmly in the camp of the sceptics. As recorded in his second book about Japan,

The Playground of the Far East, he had personally seen no relic landforms during his mountain travels in Japan. All in all, the evidence for ancient glaciers was “slight and inconclusive”, he wrote, and, therefore, “it seems reasonable to conclude that the claims that have been advanced on behalf of glacial action in the Japanese Alps are not as yet sufficiently substantiated to merit acceptance.”

Although Weston published these words in 1918, long after his return to England, he most probably formed his opinions long before. During his second stay in Japan, he had taken an interest in the glacier debate and, just before leaving the country in May 1905, he had received an English version of Yamasaki’s original 1902 paper. According to Kojima, who commissioned the translation, Weston was unimpressed by the evidence presented there.

Whether or not Kojima was influenced by Weston, he certainly stayed true to his friend’s position. While never finally excluding the possibility that glaciers had once existed in Japan, he kept firmly to a neutral stance on whether the evidence adduced by the glacier enthusiasts actually supported that conclusion. And, as Ono Yugo points out, some of Kojima’s reservations about that evidence were well founded. For example, the moraine-like rubble heaps found within the basins of some Japanese cirques are not actually moraines – rather, they are “ramparts” formed from stones bouncing and rolling down from the snowfields above.

![]() |

| Alfred Hettner |

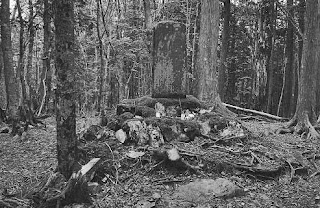

But the case for ancient glaciers did not rest only on cirques. Soon after the “Sangaku” debate, geologists started to find signs that glaciers had once reached much lower altitudes. In 1913, Alfred Hettner, a visiting German geographer, found a scratched-up boulder in the Inekoki gorge of the Azusa River, above the village of Shimajima. Glacier supporters interpreted it as evidence for an ancient moraine; naysayers said that water erosion could equally well account for the stone’s markings.

In 1931, Ogawa Takuji, a geologist at Kyōto University, published a paper arguing that ancient low-altitude glaciers had created the moraine-like debris found at around the 1,000-metre mark on Yatsu-ga-take, an extinct volcano, and at other sites in Nagano Prefecture. This time, the case was strong enough to prompt a renewed search for glacial relics throughout the Japan Alps and in Hokkaidō.

![]() |

| Ogawa Takuji |

One such foray was made by none other than Tsujimura Tarō, who had recently succeeded his mentor Yamasaki as professor of geography at Tōkyō University. For the locus of his search, he chose Senjō-dake in what were now known – irrevocably, thanks to Kojima – as the Southern Japan Alps.

Climbing into one of Senjō’s elegant cirques in the summer of 1932, Tsujimura found the evidence he’d been looking for: so-called “gekritztes Geschiebe” (scratched-up debris) in the terminology borrowed from German geologists. The parallel grooves on their smooth granite surfaces clearly showed that these boulders had been ground under a body of moving ice.

Five years before the Senjō discovery, Kojima Usui had returned to Japan after a twelve-year stint as manager of the Yokohama Specie Bank’s branches in San Francisco and Los Angeles. The chance to see live glaciers in America’s coastal ranges had not changed his mind on the question of ancient ice-streams in Japan. That didn’t stop him from continuing to write voluminously about the artistry of snow and ice in the mountains.

Just a few months before Kojima’s death in 1949, he returned to the glacier question in an essay on “The Hettner Stone revisited”. His last words on the matter hint at a softening in his stance:

“If these cirques and roches moutonnée were to affirm the former presence of great glaciers in the Hida, Kiso and Akaishi ranges, then there would be nothing for it but to bow down our heads at the infinitely creative ways of Nature, this strange and mysterious shaper.”ReferencesMain source is Ono Yugo (2010): Kojima Usui and Tsujimura Taro — Arguments in “Journal of the Japanese Alpine Club (Sangaku)”over glacial landforms in the Japanese Alps. Journal of the Japanese Alpine Club( Sangaku),105,138-154.(in Japanese)小野有五(2010): 小島烏水と辻村太郎—日本アルプスの氷河地形をめぐる『山岳』での論争—.山岳,105,138-154.

For the importance of Ogawa Takuji’s 1931 paper, see R H Grapes, History of Geomorphology and Quaternary Geology, page 185.

For account of research on Senjō-dake, see Tsujimura Tarō's 1961 paper in Chigaku Zasshi (辻村太郎、本州山地の氷河堆積物)

![]() Surly and turbid was the mood of the Tamba River, swollen by the June rains. A sneak eddy had already taken down N-san. He bobbed up again, but not his spectacles, alas.

Surly and turbid was the mood of the Tamba River, swollen by the June rains. A sneak eddy had already taken down N-san. He bobbed up again, but not his spectacles, alas.![]() Climbing round the impasse didn’t appeal; the gorge was sheer. As for hauling oneself upstream, no crack or hold came to hand on those slimy walls of chert. Try as we might, the river kept flushing us back into that foaming pool. Eventually, we had to give up – we’d come back when there was less water.

Climbing round the impasse didn’t appeal; the gorge was sheer. As for hauling oneself upstream, no crack or hold came to hand on those slimy walls of chert. Try as we might, the river kept flushing us back into that foaming pool. Eventually, we had to give up – we’d come back when there was less water.![]() Back at home, reading a ‘how-to’ book, I realised we’d lacked a vital piece of kit. That’s right; the humble drain unblocker. Slap one onto a hopelessly smooth wall (see right) and you can haul yourself forward against raging torrents of moving water. Indeed, the slimier the rock, the better it sticks.

Back at home, reading a ‘how-to’ book, I realised we’d lacked a vital piece of kit. That’s right; the humble drain unblocker. Slap one onto a hopelessly smooth wall (see right) and you can haul yourself forward against raging torrents of moving water. Indeed, the slimier the rock, the better it sticks. Surly and turbid was the mood of the Tamba River, swollen by the June rains. A sneak eddy had already taken down N-san. He bobbed up again, but not his spectacles, alas.

Surly and turbid was the mood of the Tamba River, swollen by the June rains. A sneak eddy had already taken down N-san. He bobbed up again, but not his spectacles, alas. Climbing round the impasse didn’t appeal; the gorge was sheer. As for hauling oneself upstream, no crack or hold came to hand on those slimy walls of chert. Try as we might, the river kept flushing us back into that foaming pool. Eventually, we had to give up – we’d come back when there was less water.

Climbing round the impasse didn’t appeal; the gorge was sheer. As for hauling oneself upstream, no crack or hold came to hand on those slimy walls of chert. Try as we might, the river kept flushing us back into that foaming pool. Eventually, we had to give up – we’d come back when there was less water. Back at home, reading a ‘how-to’ book, I realised we’d lacked a vital piece of kit. That’s right; the humble drain unblocker. Slap one onto a hopelessly smooth wall (see right) and you can haul yourself forward against raging torrents of moving water. Indeed, the slimier the rock, the better it sticks.

Back at home, reading a ‘how-to’ book, I realised we’d lacked a vital piece of kit. That’s right; the humble drain unblocker. Slap one onto a hopelessly smooth wall (see right) and you can haul yourself forward against raging torrents of moving water. Indeed, the slimier the rock, the better it sticks.