A memoir of life on Mt Fuji by Hirai Yasuyo, former head of the summit meteorological observatoryI worked 40 years for the Meteorological Agency, much of that time in work related to the Mt Fuji summit observatory. After retiring to my native Izu, I like to look out for Mt Fuji whenever I’m somewhere the mountain should be visible from. These days, it’s often hazy whatever the time of year and I don’t see the mountain as often as I used to. When I do see its distant shape under a clear sky, it’s like meeting an old friend, and I remember all the things that happened up there and all the people I used to know.

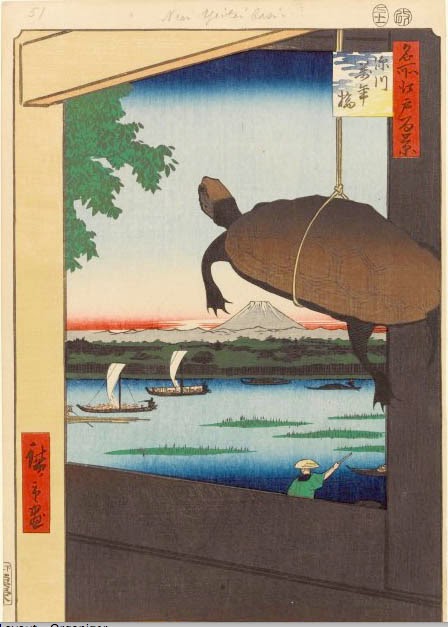

![]() |

| Porters above Hoei-zan |

I came to the summit observatory quite by chance. A magazine that I used to look at in my school’s reading room sometimes serialized novels by Nitta Jirō, and that was how I first heard about the observatory and got the idea that I’d like to work there.

In 1954, I was hired to make weather observations at the Meteorological Observatory on Izu Ōshima island. In those days, that meant taking temperature and pressure readings at set times in a set order, and also making visual observations of weather phenomena. I remember sweating quite a bit over those visual assessments of clouds and sky conditions.

As the observations had to be made rain or shine, I sometimes sheltered under an umbrella as I made my measurements out there by the instrument box. Until, one day, I heard one of my seniors comment to a team leader as follows: “The young guy seems to be out there at the instrument box with an umbrella. But we used to just stand out there in the wind and rain making our observations, didn’t we.” After that, I decided that I would go out into the wind and rain like that, so that I could feel the weather unsheltered.

![]() |

| On the way to the summit |

Around that time, I applied for re-assignment to the Mt Fuji observatory, and so all of a sudden I was able to realize my dream of working at the summit station. And so, on April 5, 1956, I stepped off the train at Gotemba and was overwhelmed by the snow-covered bulk of the mountain.

Next day, before dawn, we left the refuge hut at Tarobō for what was to be my first-ever Mt Fuji climb. We had to break trail through the snow on the slopes of Hōei-zan before taking a break for breakfast at the refuge hut above the Seventh Station. From the Eighth Station onwards, on a stretch they called “Tarumi”, we were climbing on a steep sheet of blue ice. By the Ninth Station, I was so close to collapse that I was barely making sense any more. In fact, I tripped and fell over, but somebody who came to meet us quickly stopped my feet sliding with his axe, so that nothing worse happened.

The sun was low by the time we reached the summit station. Ash-grey clouds floated past under the darkening sky and a weird “bōōō” sound emanated from the depths of the vast crater. Laying eyes on this scene for the first time in my life, I could hardly believe that it belonged to this planet.

![]() |

| De-icing duties |

My apprenticeship in the ways of the observatory started on the morning after a blizzard. The first job was to bash the accumulated hoarfrost from the instrument tower. “This is how we do it,” grunted a colleague, as he grabbed a wooden mallet and started pounding at the steel framework, sending the ice shards flying with the vibrations. This is just the hoarfrost you always get when clouds come drifting across a summit and their supercooled droplets freeze onto any object they meet, creating an ice build-up. Up here, though, just about everything that projected above the ground would ice up – the frost was everywhere. Every time a low pressure came along the Pacific coast in winter or spring, that instrument tower would rime up overnight to a depth of several tens of centimetres.

This “de-icing” was the toughest work all through the snow season. When the ice shards blew back in your face, the pain was like needles thrusting into you. At first I relished the work as something you’d only get to experience on summit duty, but later as the gales pierced me to the core and the effort made me struggle to breathe, this job started to grind me down. Up there, on that tower, hacking at the ice in the pitch dark, I’d start thinking “Why does it have to be me? Does anybody care that I’m way out here battling the ice on top of Fuji?” It was at those times that the sheer isolation of Japan’s highest summit would get to me.

![]() |

| The radar dome in winter |

In those days, Fujimura Ikuo, the observatory head, would sometimes come up and tell us that weather phenomena were never the same twice – if you don’t record them at the time, they’re lost forever, he’d say, to impress on us the seriousness of our responsibility and mission as meteorological observers. He’d also say, when the team was trying to bash every last scrap of ice from the instrument tower, that we should only clean things up as far as was needed for good measurements. In fact, we should go as easy as possible. “If you drive yourselves too far, you’ll not last long on summit duty,” he told us. After that, I decided to give the job about 80%, so that I could always keep something in reserve. And I think that this was one reason why I was able to continue serving so long on the summit.

My summit duty years started in 1956, when I applied for the transfer from Izu Ōshima. Then, after stints in Tokyo, I was up there again from 1960 to 1964 and from 1971 to 1983. Adding in the years that I spent at the Mt Fuji base offices, I spent more than 30 years in work that involved the summit station. As these years spanned Japan’s economic high-growth period, I witnessed a great deal of change in both society and life at the summit station during this time. In 1964, radar and automated weather measurement systems were installed, which meant that the work changed from taking readings manually to maintaining and monitoring the measuring equipment. As for our living environment, this changed dramatically in 1973 when the new building was completed and the electricity supply upgraded. Instead of the old building, where the only place you didn’t feel cold was next to the charcoal stove, we had a fully airconditioned new building, where you could sleep in a warm room. Compared with the old building, where you had to creep into bed under a frosted-up futon, this was undreamt-of luxury.

![]() |

| Automation comes to Mt Fuji |

Other innovations included better mountaineering kit and safety measures, and we introduced a SnowTrac for the first part of the haul up the mountains. And our logistics were revolutionized when we started using the bulldozers to freight up supplies in summer, leading to a dramatic improvement in both the quality and quantity of our food. In winter, though, the weather could still cause delays in the food supply, and I have fond memories of a three-day stretch where we had nothing to eat with our rice except salt-dried squid and soy sauce.

![]() |

| Dining area in the summit weather station |

As for mountaintop itself – the wind, the cold and the thin air – nothing could change that. Climbing up and down the mountain in winter during the shift changes was pretty much as tough as it was in the early years of the summit station. And, even though the instruments had been modernized, things went on icing up just as before, so that the only way observations could be kept up was for the summit team to go out in the same old way to bash at the ice encrustations on the instrument tower and the radome.

![]() |

| Change of shift |

Yet I did see changes during those thirty years, even if only gradual ones – little rockslides around the summit, new fissures opening up in the crater and the Great Gully of Ōsawa, and so on. And there was the way that the knotweed (オンタデ、Aconogonon weyrichii) and other alpine plants kept creeping up the mountainside, bit by bit, towards the summit.

Some things changed more rapidly. One was the spread of the town lights below. Up until the late 1950s, except for the Tokyo-Yokohama area, you could distinguish the lights of one town from those of another all along the coast at night. In the 1960s, however, the lights started to spread into the dark patches between towns, and from the 1970s the whole Kantō plain as far as Enshū became just a single mass, a sea of light.

Another of those changes was air pollution. When I first climbed the mountain in 1956, there was a splendidly clear view all round. Under that azure sky, you could gaze down at the whole Kantō spreading out below, at the Chubu mountain ranges, and the islands of Izu floating on the ocean. In those days, we had to make a visual assessment of the visibility below us, how high the haze came up and how thick it was. You could clearly see the upper limit of the haze as a sharp dividing line against the sky, and we used to record its height against the backdrop of the Akaishi mountains. In the 1960s, the height and density of the haze might have fluctuated a bit, depending on conditions, but it rarely swamped the 3,000-metre ridgeline of the Akaishi mountains.

In 1971, when I came back for summit duty after a seven-year gap, I was in for a shock – there were now many more days when the haze buried the mountains and you couldn’t see the ground below, even when the sky was cloudless. Air pollution had become a serious problem in Tokyo from the early 1960s; now you’d often see a thick haze layer in all directions.

Haze layers develop when you have the right meteorological conditions, such as several days under a ridge of high pressure, but it’s not the weather that has changed around Mt Fuji. Rather, the spreading haze is coming from the increase in sources of pollution and the growing volume of polluted air.

In former days, you could always expect to see Fuji from Izu, but I feel that in recent years that’s no longer true. And, as I’ve spent most of my life involved with Mt Fuji, I can’t help feeling that we’re losing something of great value.

Seeing Mt Fuji obscured by haze isn’t just about losing a view – it’s a sign that air pollution and environmental destruction are getting worse. My hope is that, by continuing our scientific observations, we can shed light on the state and causes of that environmental degradation, so that we can finally do something about it.

References

Translated from "Harukana Fuji-san wo nozomeba" in (ed) Dokiya Yukiko,

Kawaru Fuji-san Sokkojo, 2004. Images are also from this book.